When Was Gauguins First Art Show of Tahitian Art?

Paul Gauguin in the Tropics

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

In the spring of 1891, an elegant and comfy ship called Océanien was crossing the Indian Ocean en route to the French colonies in New Caledonia. Its picturesque passengers, divided into three classes under the deck, included wealthy, important functionaries and landowners; and young people of humble origins who traveled to the colonies searching a hereafter they did non find in the one-time France. In other words, the transoceanic ship was sort of a human zoo, a circus with then many actors that nobody noticed the presence of a middle age man with a large moustache, who spent the endless hours sitting on the deck, gazing into the horizon. Nevertheless, that bearding personage who occupied 1 of the humble third-class cabins was non an ordinary passenger. He was an admired painter called Paul Gauguin, who travelled to Tahiti searching an artistic redemption, a improvement to the primitive and the exotic life that could aid him to notice a way in which his Art would be purified. In his own words, "The West is rotten (…) and anyone who experience like Hercules could find new strengths travelling to far-abroad places. Then come up back one or two years later, strengthened"

The life and works of Paul Gauguin in Tahiti and the Marquises

Nevertheless, Gauguin's trip was not exactly a "poor human being's odyssey". In fact, he asked the French ambassador to personally welcome him at Papeete 'southward harbour, as an official invitee of the French Authorities. In addition, Papeete -the Tahitian upper-case letter- was non the tropical paradise that it could have been decades before, the exotic and mysterious town described past swell travellers like the legendary Captain Cook. No, Gauguin soon realized that such paradise had been "killed" later many years of noncombatant, military machine and religious colonization. However, he could still find -in rural areas far enough from the uppercase- an of import part of the "exotic" and "primitive" civilization Gauguin was searching.

WAS GAUGUIN A COLONIZER?

In the final decades, some art critics and historians have criticized Gauguin's paternalistic attitude during his starting time years in Tahiti (when he described Polynesians as "meek" and even "fool"), comparing him to the first colonizers, who aggressively tried to impose the laws and faith of the Old Continent.

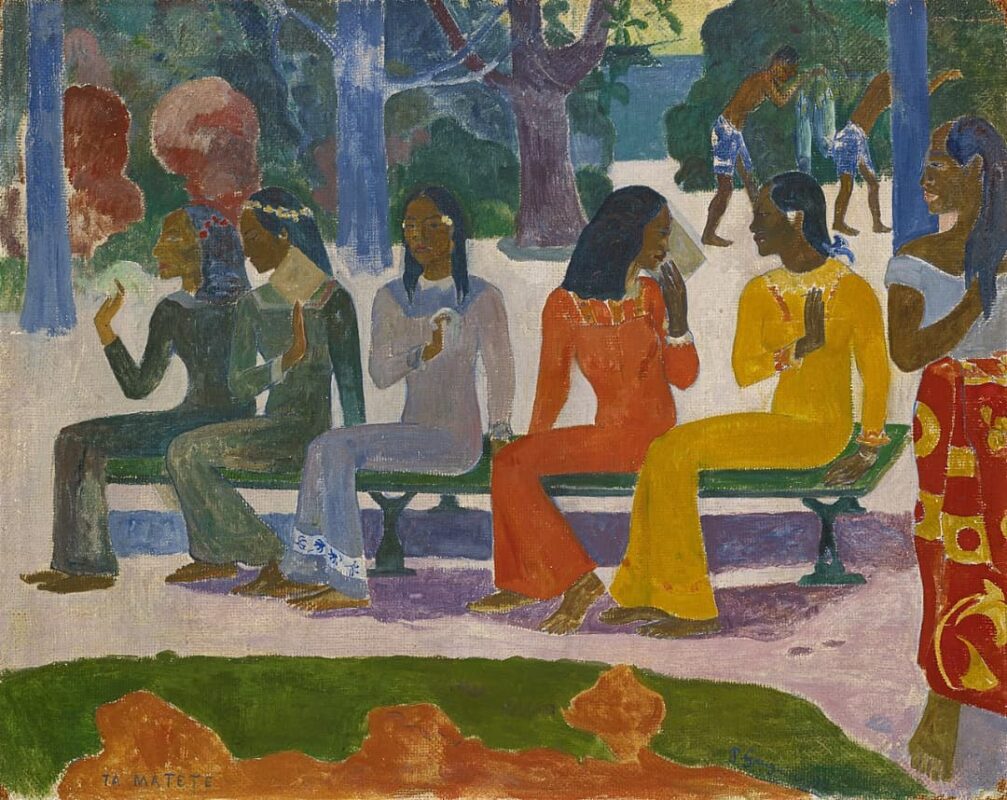

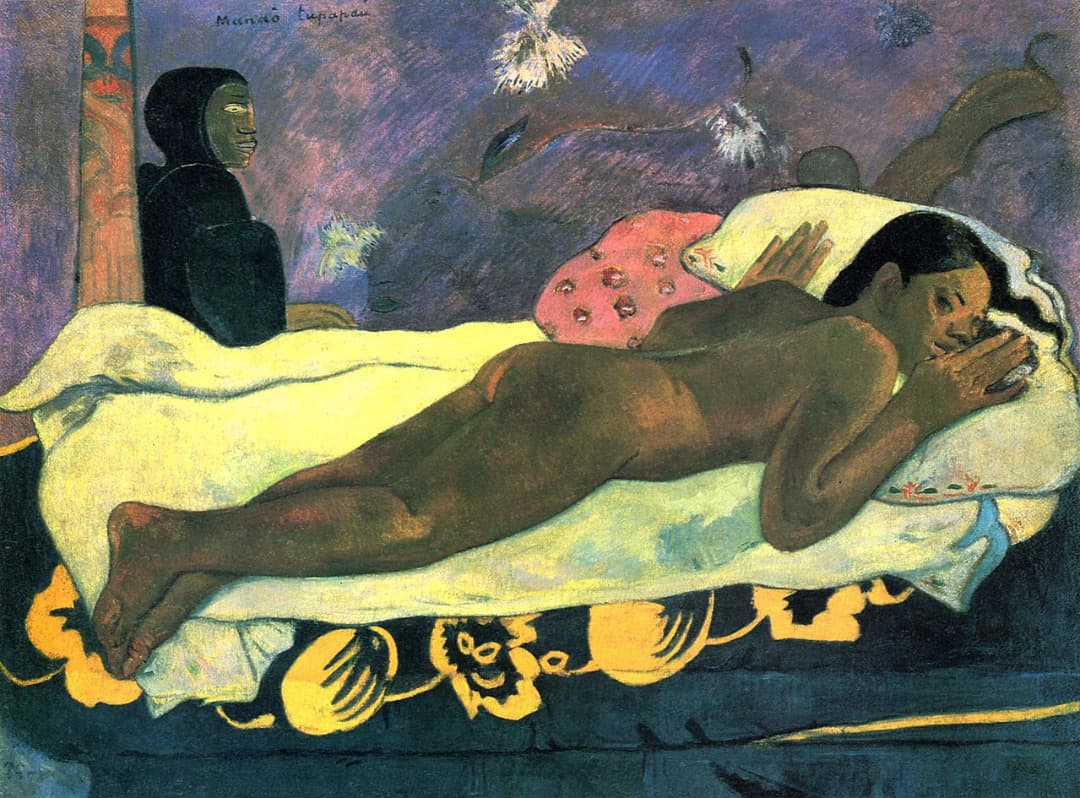

In "Ia Orana Maria (Salve, Maria)" (New York, Metropolitan Museum ), a work painted during his first yr in Tahiti, Gauguin transferred the Cosmic iconography into the exotic Southward Pacific. The Madonna, the child, and fifty-fifty the two women in adoration and the golden-winged angel in the groundwork, are clearly Polynesian natives. Here Gauguin introduced the Catholic Faith into the local culture, making the natives the protagonists of this typically Western religious scene. Nevertheless, this painting, its composition being quite dissimilar from those of the European tradition (to the indicate of that we can non determine with certainty if information technology is an "Annunciation" or an "Adoration") is followed by many works in which the local tradition of the natives is the protagonist, like in "Manao tupapau" ("The spirit of the dead watches you lot", Buffalo, Albright-Knox Art Gallery), considered by Gauguin himself as 1 of the masterworks of his starting time Tahitian period. The creative person described the painting with these words: "This people have a traditional fear to the spirit of dead people (…) I have represented the apparition as a elementary petty woman because the daughter (…) can only see it as a person that she met, a person like herself".

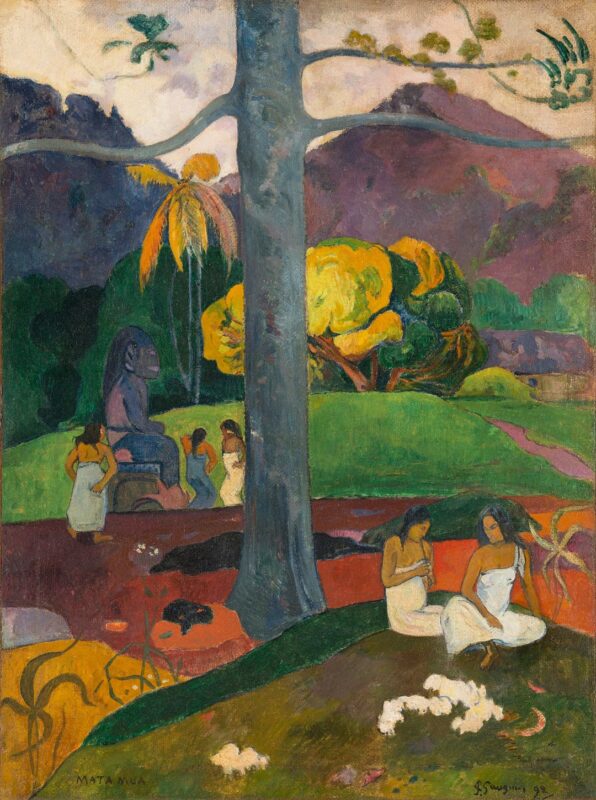

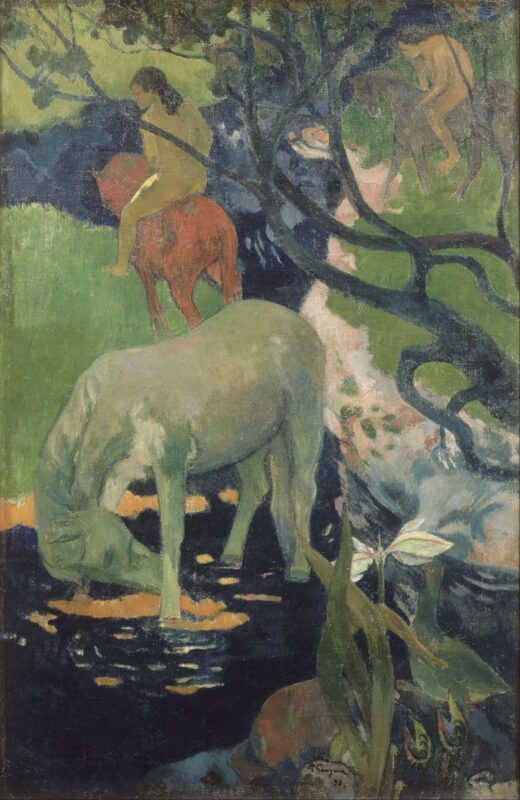

With this painting, Gauguin progressively abandoned the Catholic iconography and began introducing himself into the native tradition , although he temporary recovered the Christian themes in paintings such as "Te Tamari No Atua (The birth of Christ") (Munich, Neue Pinakothek) or "Maternité" (two versions, one in the Ermitage and some other sold in 2004 at Sotheby's for $39.2 one thousand thousand). These bequeathed beliefs achieved a predominant position non merely in his artistic oeuvre, merely also in his personality. The Catholic "colonizer" turned into a ferocious detractor of the Catholic Church, while in his interior he began to accept the local native beliefs, as we tin see in "The white horse" (Paris, Museé de Orsay), or in the supreme "Matamua – in olden times-" from the Thyssen collection, which depicts a legendary valley in the middle of the island, in which its inhabitants "still live as in past times"; or in the many statuettes of Gods and idols that he made in the post-obit years.

IDOLS AND GODS

In the last years of his life in the Marquises, Gauguin wrote about the Polynesian sculpture tradition: "This Fine art has disappeared because of the missionaries, who considered those sculpture (…) fetishism, an offence to God". He was right. In fact, at the cease of the 19th century, virtually all the ancient Polynesian wood sculptures had been destroyed past the devastating Christian missions. Gauguin embarked on an ballsy work: returning the natives to their destroyed mythology.

Unfortunately, almost all the sculptures Gauguin created in Tahiti were carved in low-quality wood, which caused its premature destruction. Still, the Orsay Museum in Paris conserves two piddling statuettes of this creative menses: the "Idol of the shell" and the "Idol of the pearl". The date of both sculptures, although inexact, tin can be situated effectually 1892. In both figures Gauguin has represented the Polynesian god Taaroa, whose beat contains -according to the Polynesian tradition- the entire universe. But it was in 1894, back in Paris (we volition talk most this comeback in the side by side affiliate) when Gauguin created his undisclosed masterpiece in sculpture: the statuette of "Oviri" (Paris, Orsay Museum), a sinister representation of the Polynesian God of the decease and the mourning. The figure, which Gauguin called La Tueuse (The killer) is a disturbing female person figure of primitive and crude gestures, long hair and huge eyes, which stands over the terrific figure of a dead wolf.

Only this iconographic recuperation that Gauguin began is not only visible in the three-dimensional works: in the following years, the artist transferred this "recovered" iconography to his paintings, where he institute more than possibilities: in the canvas, the gods and idols could change its scale, turning into the main protagonists of the scene ("The day of the gods", 1894); or in spirits every bit agonizing apparitions ("Riders in the beach", 1902)

THE Interruption IN FRANCE

But Gauguin's life in Tahiti was far from existence paradisiacal: in addition to the heartrending confinement and his perennial economic difficulties, during the concluding months of 1892 Gauguin became seriously ill, losing sight and suffering constant diarrheas and coughing up of blood that forced him to be hospitalized for many months. Desperate, he wrote to the French Ministry begging him for a repatriation that took place at the stop of the following twelvemonth.

Dorsum at dwelling house, and after being hospitalized in Paris in much better sanitary conditions than in the Polynesian islands, (and later receiving the inheritance of his uncle Isidore), his physical and economical situation improved. He rented an apartment in Paris and lived there with Annah the Javanese. In improver, Gauguin exhibited 50 of his works in an of import exhibition of modern Art in Copenhagen. In other words, nobody could suppose that Gauguin'southward risk in the Polynesia could be repeated.

But Gauguin returned. He returned two years subsequently, later discovering that he had contracted syphilis. He returned afterward a brawl in which his ankle was cleaved. He returned later on painting in Paris a praise, a fantasy of the Tahitian civilization, the masterwork entitled "Mahana no Atua (The 24-hour interval of the gods") (Chicago, Art Establish), in which the goddess Hina is adored by a grouping of women who dance surrounded by multicolour waters. In short, he returned afterward realizing that his identify was no longer among the European people. "What a stupid way of life, the European style of life!" On April 3rd, Gauguin left Europe, never to render again.

"I AM A CRIMINAL" – Dorsum IN TAHITI

"I want to terminate my life here, in the confinement of my shack. Oh yes, here I am a criminal, but… what is wrong with that? Michelangelo was too a criminal."

Back in Tahiti, Gauguin felt liberated, costless of any artistic or social corset. In his progressive separation from any vestige of the European social club, he left Papeete and moved to a sack in the middle of the countryside, perhaps searching that fabulous valley he had depicted in the "Matamua".

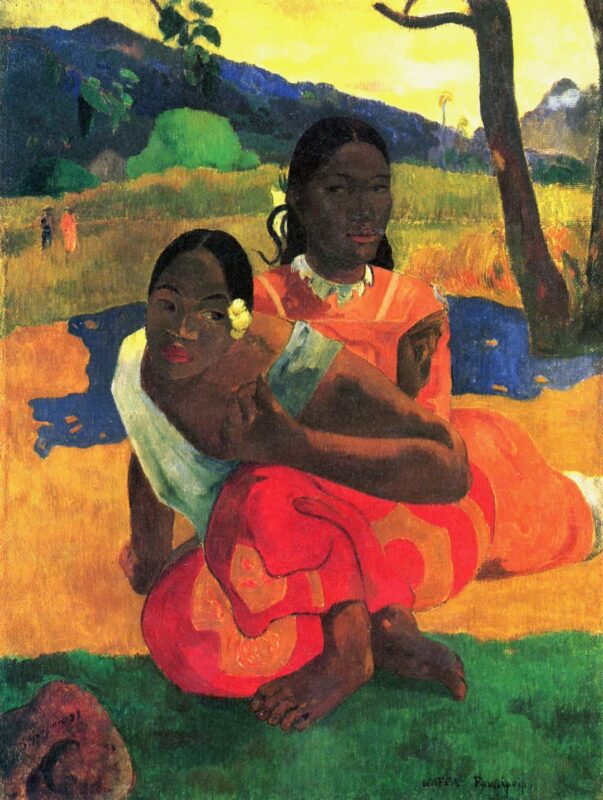

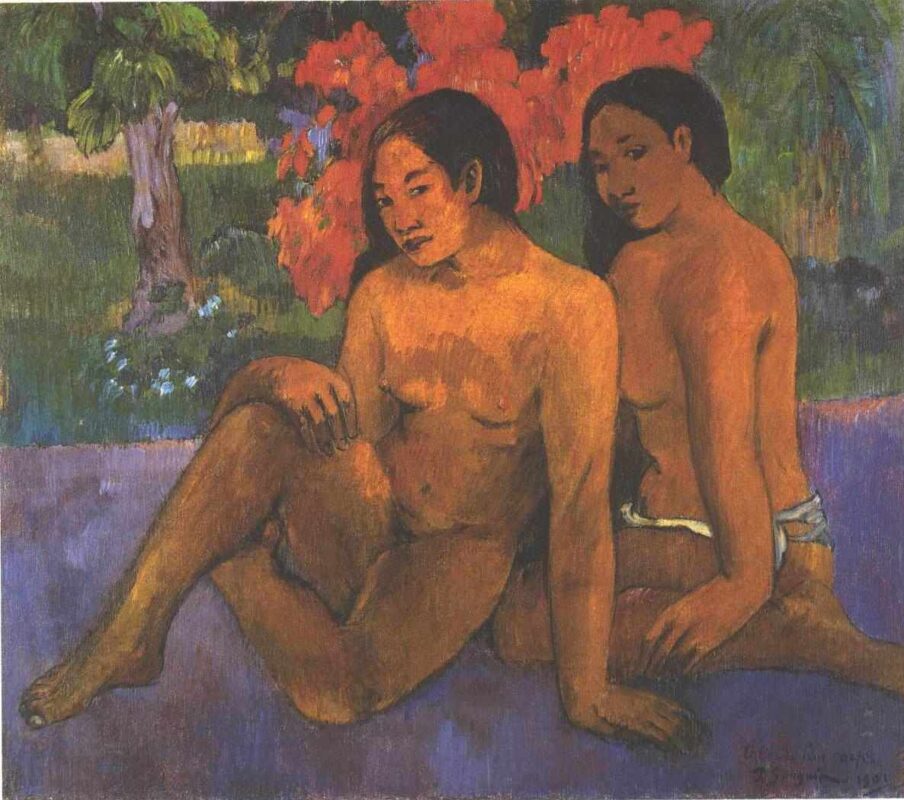

Free of these social conventions, Gauguin created a new "Eve" using Tahitian women as his model. The creative person had never hidden his admiration for Tahitian immature women, even for the too young ones (his lover Pau'ura was simply 14 years one-time), and, during his French intermission, he boasted in front of his friends most his conquests, saying that every night several Tahitian girls jumped into his bed "equally possessed by evil spirits" (an attitude that gave him a nice syphilis). The female person figure is the protagonist in works like "Te arii Vahine (The queen of the beauty") (1896, Moscow, Pushkin Museum), "Girls with mango flowers (or Two Tahitian)" (1899, New York, Metropolitan Museum.)

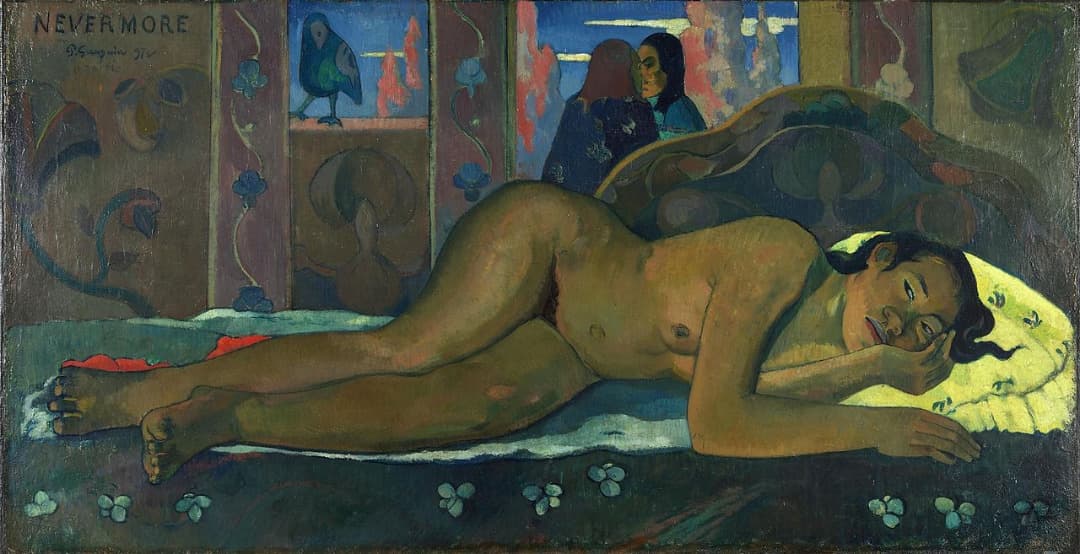

Some other paradigmatical piece of work of this period is the famous "Nevermore" (1897, Courtauld Found Galleries, London), a piece of work in which the female person nude is still visible. Nevertheless, something from the quondam Europe is still nowadays in the piece of work: the painting pays tribute to the famous poem past Edgar Allan Poe, which Gauguin had listened at the Café Voltaire in Paris. However, the raven -main protagonist of Poe's story, in which it is depicted equally sinister and menacing- is in Gauguin's canvass not as important every bit the strong and vibrant female nude.

WHERE Do WE COME FROM? WHAT ARE WE? WHERE ARE Nosotros GOING?

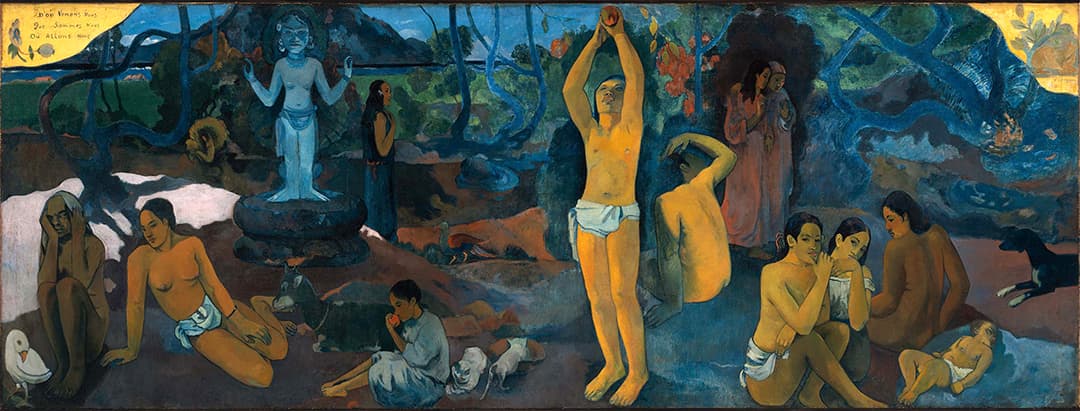

Paul Gauguin affirmed that later on painting "Where practice nosotros come from? What are we? Where are we going" he tried to commit suicide. Nosotros practice not know for certain if that confession was true or not, but information technology is a fact that just before painting his masterwork, a serial of events followed each other in a dramatic sequence, as presaging a tragic end that would happen 5 years afterward. Get-go, his economic state of affairs became extremely difficult –however, he rejected an important amount of money offered past the Ministry because he considered it a "charity"- while the syphilis and the alcoholism turned his physical state of affairs into a torture. Nevertheless, the worst hit arrived by mail: in the spring of 1891, a letter informed him of the expiry of his daughter Aline, age 21. This tragic event provoked not only the break-upwards with his wife –Gauguin irrationally accused her of Aline'southward death- but also his definitive rupture with any vestige of faith. In a devastating letter of the alphabet wrote that yr, Gauguin affirmed: "My daughter is dead. At present I don't need God."

In such psychical status Gauguin embarked on the ballsy mission of creating his artistic testament, a piece of work that resumes all his other creations: Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? is not only the about jumbo canvas ever painted by Paul Gauguin, but it's also the piece of work that explains the unabridged philosophical and pictorial doctrine of the artist.

In a hitting horizontal format, the canvas follows an inverted chronological order, get-go at the left corner with the heartrending effigy of an ancient mummy in fetal position, her ears covered with her hands; while at the right corner, a baby, symbol of the life and the innocence, is surrounded by iii Tahitian young women. At the center of the picture, the figure of a man who takes a fruit symbolizes the temptation of the man. Structuring the sheet in an inverted chronological order, Gauguin seems to bespeak the primitive, the innocent, as the only one way for the artist.

THE Terminal CHORD – FLIGHT INTO THE MARQUISES

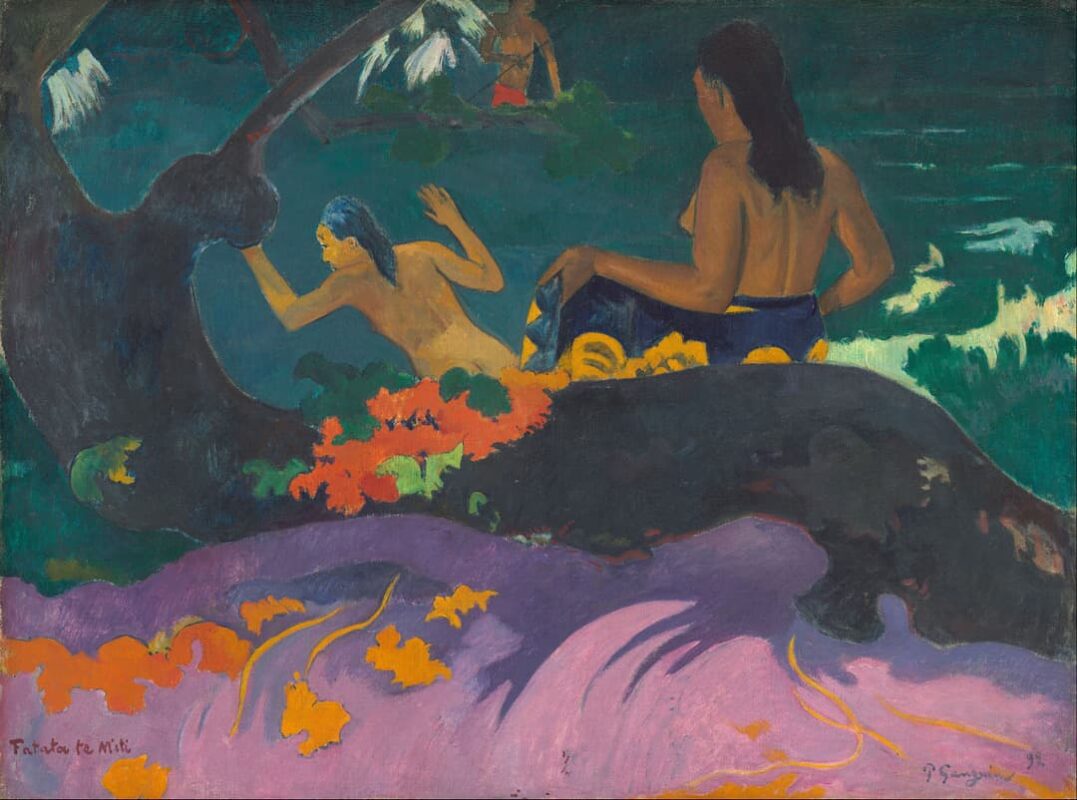

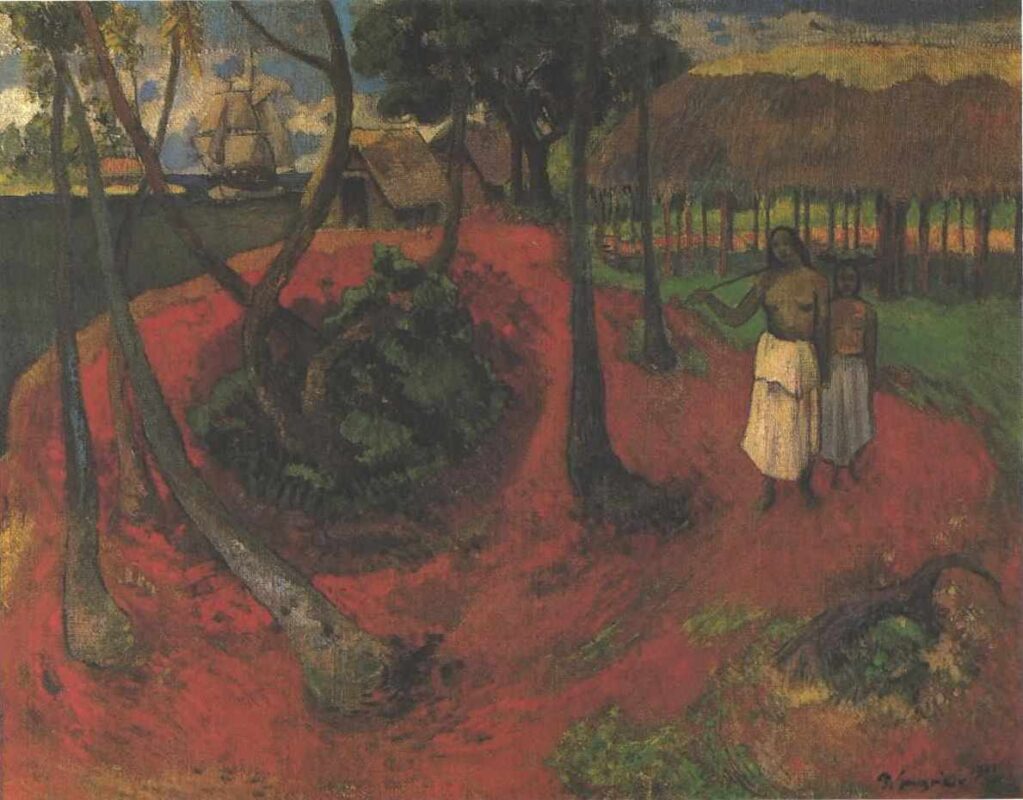

In September 1901, Gauguin left Tahiti and took up his residence in the Marquises Islands. The reason of this flight is withal not antiseptic: while his admirers suggest that the creative person was seeking a new stage to his artistic concerns, many historians have noted that his concrete deterioration was so evident that his popularity among Tahitian girls was below zero, forcing him to long periods of forbearance. Anyways, Gauguin established himself in Hiva Da, the principal isle of the Marquises archipelago, in lands endemic by the Church. Just earlier his trip, he painted a beautiful goodbye to Tahiti in his " Idyll in Tahiti" (1901, Zurich , E. Thou. Buhrle collection)

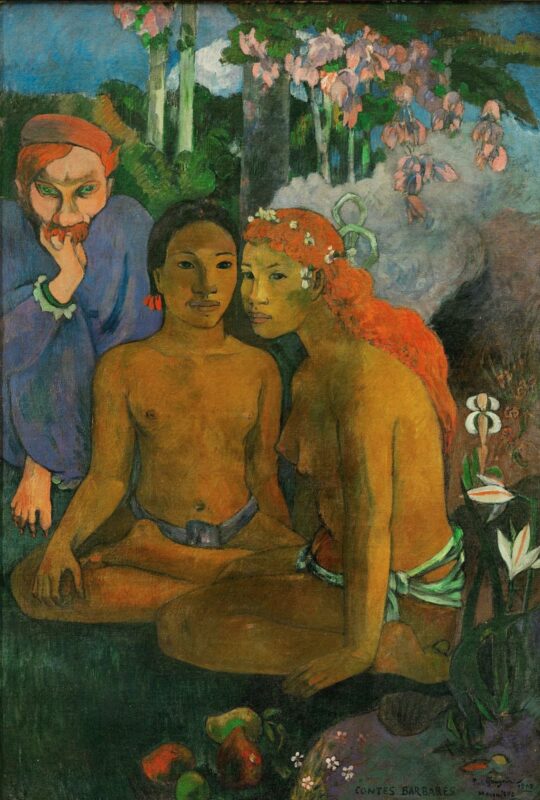

The female figure is notwithstanding a fundamental office in his artistic oeuvre. In "Contes Barbares" ("exotic legends", 1902, Essen, Folkwang Museum ), Gauguin in one case once again praised Polynesian beauty, depicting two beautiful girls, sitting in an exotic landscape. Backside them, Gauguin represented the effigy of his friend Meyer de Hann, a Parisian poet. It is quite curious that the figure of the western man is depicted as a demon with feline eyes and sharpening claws.

Withal, Gauguin was at the time outset to sense his own death: his physical deterioration was then unstoppable, and the artist was tempted -for the beginning time in many years- to return to Europe. However, he was still stiff enough to pigment. His compositions from these concluding years are full of metaphors ofdeath, as information technology is evident in his final masterwork, the two versions of "Riders on the beach" (Essen, Folkwang Museum, and Niarchos collection). In this kind of tribute to Degas racetrack pictures, Gauguin represented the riders in an apparently endless beach. The whole flick is filled with the melancholic sense of taste of a farewell, as predicting the artist'southward own death a few months later on: the riders are quietly approaching to the seaside, where a breaker wave marks the limit between land and sea -or between life and death- from where two mysterious, colour-dressed spirits have appeared, perchance to accompany the spirits in their last trip. The fancy coloured work is Gauguin's pictorial testament and an eloquent ode to the Polynesian way of life.

On May 8th, 1903, in the middle of multiple physical, economical and juridical problems, Gauguin died. The legend, non always veridical, tells that the natives, informed of the artist's death, began to shout: "Gauguin is dead! There is no paradise!"

weingartnerfrivinse.blogspot.com

Source: https://theartwolf.com/gauguin/gauguin-in-the-tropics/

0 Response to "When Was Gauguins First Art Show of Tahitian Art?"

Postar um comentário